BIOGRAPHY

Beyond the Governor’s Gallery

In my capacity as a representative of the Executive branch, my responsibilities often extended beyond the specific tasks required of the Governor’s Gallery, and I ended up being asked to serve in other capacities that fell under the arts umbrella. One which has perhaps had the most lasting legacy was my work establishing a permanent art collection for the State Capitol. This effort was initiated at the time of Capitol renovation (mentioned previously in context of the Governor’s Gallery “On-the-Road” program) as the Legislative committee responsible for the makeover sought to establish a process for selecting artworks.

While they were not bound by 1% for Art statute as they were working on a building that is not covered by this law (since is it owned by the Legislature and not technically a “State” building) the group had made the decision to set aside monies appropriated for their project in an amount at least equal to 1% and to employ an art selection process that had the same transparency and professional standards as those utilized by the Art in Public Places program. I became involved in identifying individuals to serve on a selection committee for the first round of acquisitions of works for specific areas that had been given the highest priority.

As this process unfolded it became clear to me that within the Capitol there was space to display a far greater amount of art than would be purchased initially, and I came up with the idea to establish a foundation that would carry on the work begun by the selection committee. I approached Paula Tackett, the Director of the Legislative Council Service (LCS), with my idea, and she responded quite favorably – likely due in part to the fact that she had been the person responsible for the initial decision to make art acquisition a priority. Soon thereafter, memorials directing the LCS to create the Capitol Art Foundation were passed by both Houses. The first Board of Directors consisted primarily of the initial members of the selection committee – arts professionals representing a statewide demographic and broad range of aesthetic interests – and a part-time Executive Director and collection curator was hired. |

|

|

I was subsequently appointed as a Board member by the Legislature, and during my tenure I served as treasurer and worked with the Board and Director to implement a plan to market sculpture maquettes to fund future acquisitions. The first to be offered was an edition of the Glenna Goodacre work Water Bearers, which sold out raising over $125,000. A portion of these funds were committed to the purchase of a work by Allan Houser, When Friends Meet, from which another edition of maquettes was created and sold, with part of the funds dedicated to the next acquisition, a work by Dan Namingha, Passage, from which yet another edition of maquettes was created and sold, funding the purchase of another work by Michael Naranjo, Hoop Dancer, from which another edition of maquettes was created and sold.

Writer David Steinberg summarized the work of the Foundation as follows:

Textbooks will tell you the Capitol is where the governor has his office and where the New Mexico legislature meets. What they don’t tell you is that two floors of the Roundhouse are home to a permanent collection of about 120 pieces of art. Art – all by New Mexicans – is on the walls of hallways both well-traveled and hidden. And the art is not just to see. You can relax on art furniture – chairs and couches – made by New Mexico craftsman. The Capitol Art Foundation, created by the Legislative Council, selects the works for the collection. “The foundation has always been selective in the art it chooses,” said foundation treasurer [James] Rutherford. “We’ve done that to maintain the quality and diversity of the collection.” In this case, diversity means various genre of art, ethnicity and geography of the artists. (Steinberg, 1996 - click here to view article >>)

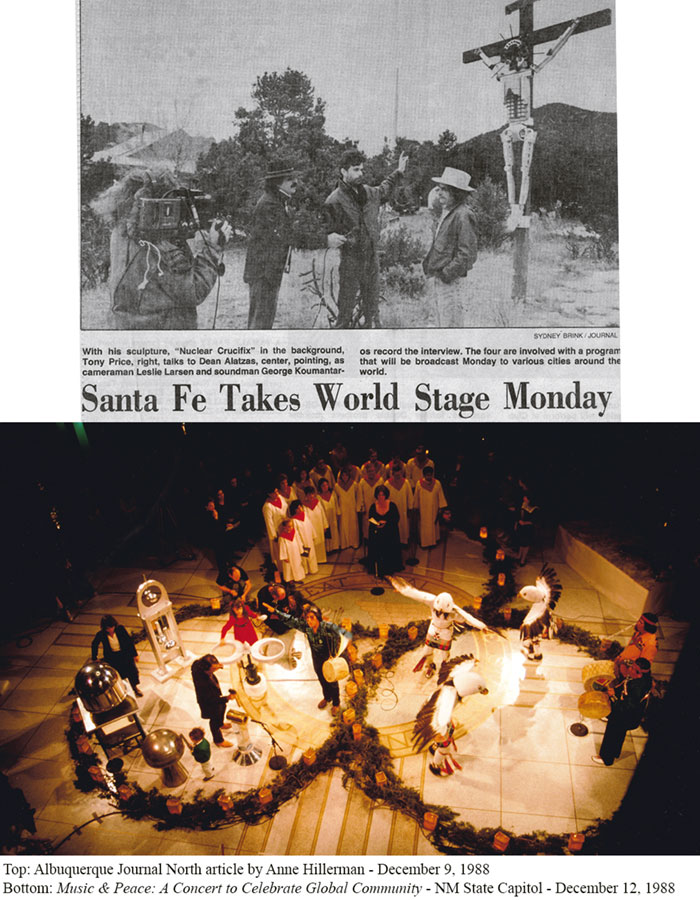

Another memorable side project involved a 1988 event entitled Music and Peace: A Concert to Celebrate Global Community organized by a group I helped form called Megavison New Mexico to facilitate Santa Fe’s participation in what was described as a “global town meeting.” The event at the State Capitol involved a satellite downlink of a live concert originating in Montreal by the World Philharmonic Orchestra, made up of musicians from 60 countries, followed by satellite uplinks from New York, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Irvine, Moscow, Geneva, and Santa Fe.

The international project was the brainchild of Joseph Godin, a pioneer of efforts in Soviet-American cooperation beginning in the late 70s, who found Santa Fe a creative community receptive to his ideas. Prior to the event, Anne Hillerman wrote of Goldin and the project:

Goldin believes that the “spacebridges” created by satellite communication and huge television screens will help the people of the world develop a leap in consciousness needed to create a planetary society. The spacebridges will re-establish the tradition of the town meeting on a global level, Rutherford said. “Things like this will happen a lot more frequently in the future – talking citizen to citizen to solve problems on the planet, based on the idea of citizen diplomacy”, Rutherford said. “We as citizens need to talk to each other, not just through political systems.” (Hillerman, 1988 - click here to view article >>)

|

|

|

In retrospect, the event was a harbinger of what was to come in terms of the technological nature of global communications – although at the time the internet and CNN were still in their infancy. While the events uplinked from other cities were more predictable by comparison, the Santa Fe event in the Capitol rotunda had a decidedly New Mexico flavor, with Tony Price tolling gongs made from nuclear weapons scrap from Los Alamos, Eagle dancers from San Juan Pueblo, and the St. Francis Cathedral choir singing Ave Maria.

Veteran New Mexico journalist, Jay Miller, described the scene thusly:

The scene inside the State Capitol last Monday night was something never before witnessed in the hallowed halls. There was more electronic recording, receiving and transmitting equipment than would be found at a Def Leppard concert. Banks of floodlights were anchored to the rails overlooking the rotunda. A dozen video monitors and two big-screen projectors were scattered around the rotunda and lobbies. Robot-like figures, crafted from the metal out of the Los Alamos National Laboratory salvage yard, stood like sentinels along the walls of the rotunda. Oddly shaped gongs, also made from salvage metal, occupied a large circle of greenery and electric farolitos on the rotunda floor. In two other circles were Eagle dancers from San Juan Pueblo and the choir from St. Francis Cathedral. (Miller, 1988 - click here to view article >>)

In the end, there were more than 60 volunteers who came together to pull off the production. It was an example of the power of ideas to bring people together around a common purpose – especially in a place like New Mexico. Many of the same volunteers would come back together a year later to host Megavison New Mexico’s next event, the Glasnost Film Festival, featuring screenings of 18 documentaries and related events honoring the visiting delegation of Soviet filmmakers.

Perhaps the most enduring project of my adult life began in 1990 when my longtime friend, Paljor Thondup – a Tibetan refugee who came to Santa Fe in the late 70s and subsequently formed the refugee relief organization, Project Tibet – asked myself and several other confidants to assist him in planning the visit of the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama had accepted Thondup’s invitation to visit Santa Fe in the Spring of 1991 to coincide with the designation by Congress of 1991-92 as the Year of Tibet to mark the 40th anniversary of the Chinese occupation of Tibet.

Coordination of the visit would be a monumental task requiring significant human and financial resources as well a sustained commitment leading up to and through the period of the visit. The various tasks and required fundraising activities necessitated the establishment of a new non-profit entity; and thus, Friends of Tibet, New Mexico (FOTNM) was born. The group organized to form subcommittees to which responsibility for various tasks was delegated, and established a timeline for the project that included early fundraising, community engagement, and a schedule of events during the 5-day visit. Since this project was considered a significant cultural event, I was given permission as a member of the Governor’s staff to devote on-duty time to the project, which uniquely positioned me to facilitate negotiations among the many entities involved and lent a certain degree of official sanction to my efforts. My involvement would again require me to set aside my own ego in order to work collaboratively and successfully allow others to share responsibility. |

|

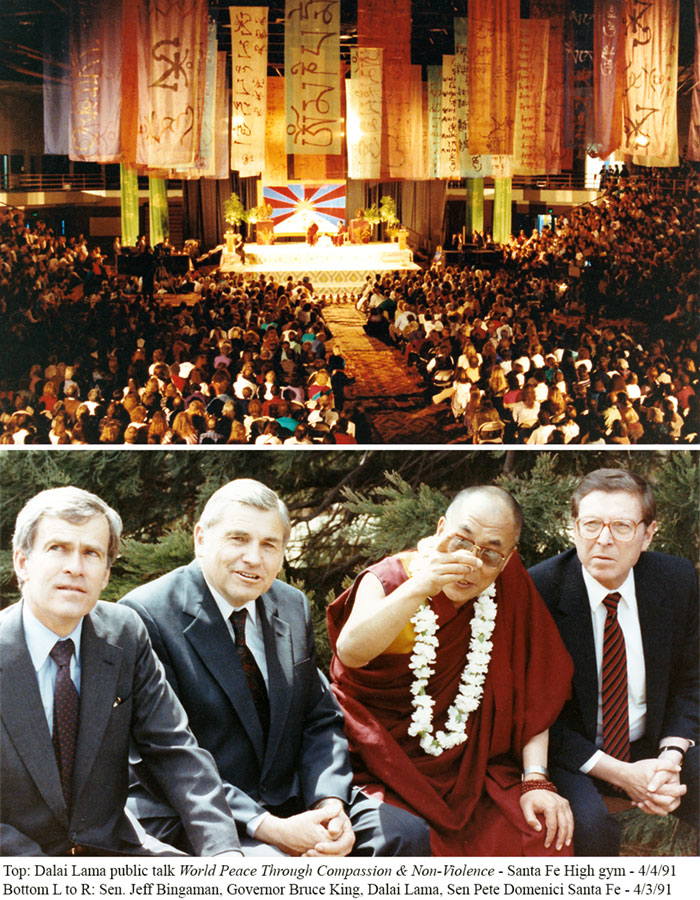

Our group’s first undertakings were: the Celebration for World Peace Benefit featuring musicians Philip Glass, Peter Rowan, Terry Allen, poet Anne Waldman, and scholar Robert Thurman at the Convention Center; a Tibetan New Year celebration at Cloud Cliff Bakery; and a benefit concert and performance at St. John’s college featuring Steve Landsberg and Nyssia Wali. In addition to generating seed money, these events provided the first opportunity to announce the Dalai Lama’s impending visit widely in the media and served as test runs for the much larger public event our group would host during the visit – a large public talk, World Peace through Compassion and Non-Violence, at the Santa Fe High School gym (the largest occupancy facility in Santa Fe) that would be made available live via satellite (click here to view article >>). This event was attended by a capacity crowd and the live broadcast was viewed by an estimated audience of several million as a result of coverage by cable networks in major cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, New York, and others, as well as impromptu events held by Tibetan organizations who rented satellite dishes.

Other events included a public talk at Popejoy Hall on the University of New Mexico campus entitled Universal Responsibility to All Things Living and Nature, a teaching at Santa Fe’s KSK Buddhist Stupa, and an historic meeting with American Indian religious and tribal leaders. The schedule also included a meeting with New Mexico political leaders including the Governor, Supreme Court Justice and Congressional delegation. This gathering would prove to be quite significant as it led directly to a meeting with President Bush – the first time a sitting president had met with the Dalai Lama – and had a significant impact on the successful efforts to pass the Tibetan Resettlement Act, which paved the way for more than 1000 Tibetan refugees to become United States citizens. |

|

|

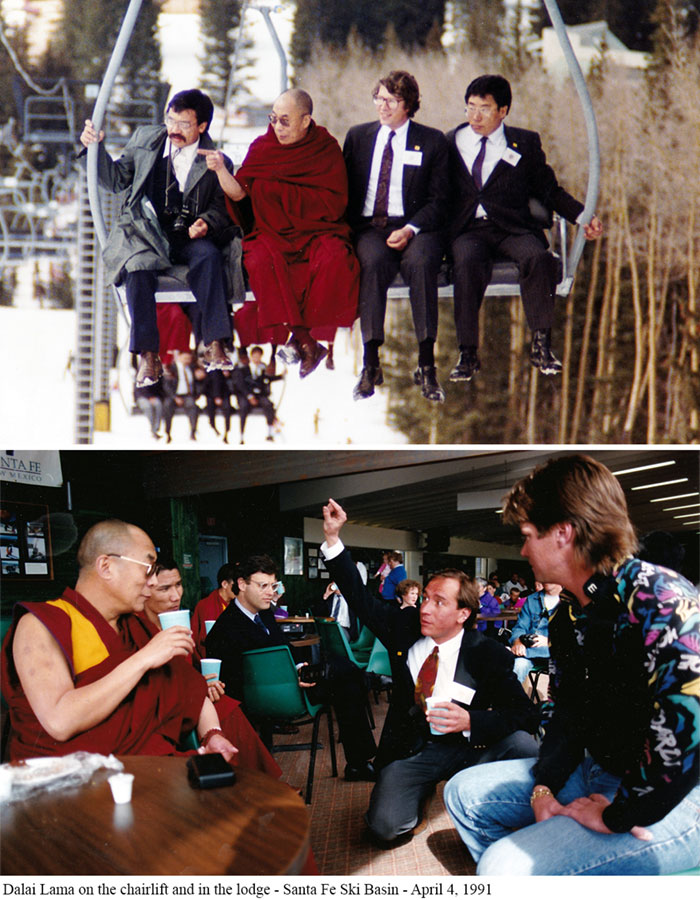

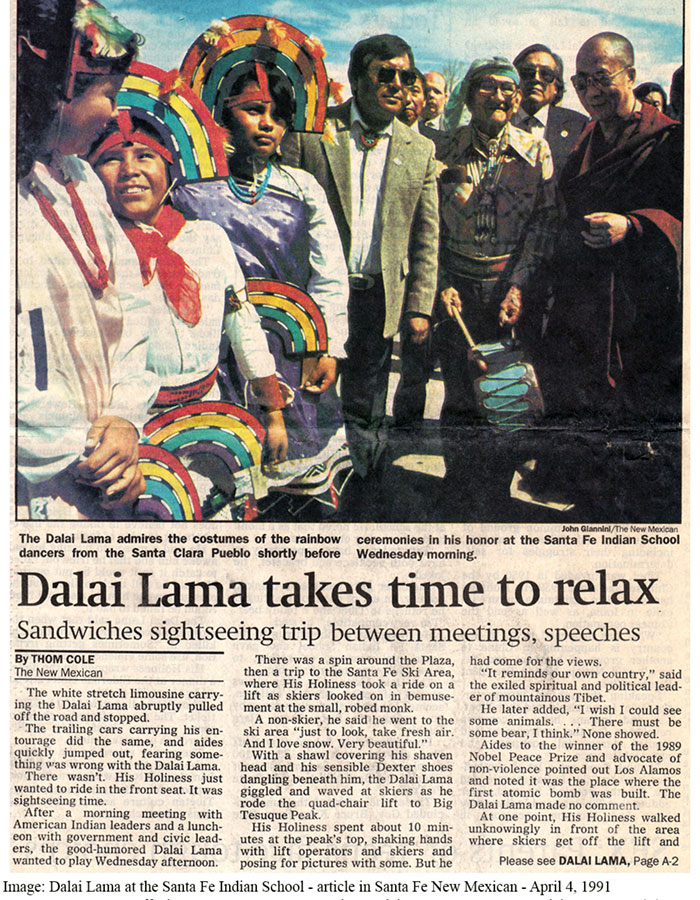

Coincidentally, it was on the way home from this event that the Dalai Lama would request his much-read-about visit to the Santa Fe Ski Basin in which he rode the ski lift to the top of the 11,000-foot mountain with myself and several monks and members of the host delegation. Author Doug Preston, who had served as press coordinator for the 1991 visit and sat next to the Dalai Lama on the chairlift, would later write an article for Slate in 2014 (subsequently reprinted in The Independent, The Week, and Reader’s Digest) in which he describes the episode as follows:

On the penultimate day of his visit, the Dalai Lama had lunch with Jeff Bingaman and Pete Domenici, the senators from New Mexico, and Bruce King, the state’s governor. During the luncheon, someone mentioned that Santa Fe had a ski area. The Dalai Lama seized on this news and began asking questions about skiing—how it was done, if it was difficult, who did it, how fast they went, how did they keep from falling down. After lunch, the press corps dispersed. Nothing usually happened when the Dalai Lama and his monks retired to Rancho Encantado for their afternoon nap. But this time something did happen. Halfway to the hotel, the Dalai Lama’s limo pulled to the side of the road. I was following behind the limo in Thondup’s car, and so we pulled over, too. The Dalai Lama got out of the back of the limo and into the front seat. We could see him speaking animatedly with Rusty, the driver. A moment later Rusty got out of the limo and came over to us with a worried expression on his face. He leaned in the window. “The Dalai Lama says he isn’t tired and wants to go into the mountains to see skiing. What should I do?” “If the Dalai Lama wants to go to the ski basin,” Rutherford said, “We go to the ski basin.” (Preston, 2014 - Click here to read full article >>)

On the Dalai Lama's visit to Project Tibet he had the opportunity to drop into the non-profit exhibition space TENGAM and meet artist Tony Price and view his Atomic Art - constructed from the detritus of the nuclear weapons at Los Alamos National Laboratories. During the encounter His Holiness was heard to quip that the artist "found a use for something that was not useful."

My involvement in this project would lead to an invitation to visit the Dalai Lama at his home in Dharamsala, India, and in the fall of 1991 I would travel there with other members of FOTNM. The month-long trip would include visits to Tibetan refugee communities and cultural sites in Nepal and India, during which I would be exposed to a rich array of Tibetan art and artifacts. |

|

These encounters in the studios of artists and craftsman in the backstreets of Kathmandu, and institutions such as the Norbulingka Institute and Kangra Art Museum in Dharamsala, had a profound impact on me, especially the time I spent looking at Tibetan art including paintings and sculpture –objects created using ancient techniques and imbued with rich symbolism. I came to understand what is meant by the concept known as darshan – that is the reciprocal experience of beholding a sacred object. These were, for me, transformational events in which I felt physical sensations I can only describe as a kind of realignment that occurred as I stood in front of thangkas containing an array of ancient Tibetan Buddhist symbols that Robert Beer describes as:

…purely an encapsulation of the manifold qualities of the enlightenment Buddha-mind, manifesting as the absolute realization of wisdom and compassion. Like a perfectly cut and many-faceted jewel that refracts myriad rays of light throughout the universe, the nature of the light is one, although its aspects of illumination appear to be many. (Beer, 1999)

These experiences added new wrinkles of awareness and insight that further deepened my understanding of the transformative power of art, and at this juncture dovetailed effectively with my recent studies related to the emerging dialogue in the field surrounding affect theory in art – a concept Kat Beavers describes in her survey of literature on the topic at once as:

…a visceral, raw pre-feeling [which] cannot be rendered by language or any other kind of transmittable information...judgement rather than an emotion…physiological things…[a] corresponding element of a preexisting object [that] arises through the evaluation of [the] thing… [which has] the capacity to collect over time as a bodily memory that can effect cognition and move outside the parameters of one’s consciousness. (Beavers, 2011)

I returned in late 1991 with a much different perspective on my life and the world, and an even larger sense of fearlessness. I think I was also worn out from the sheer volume of activity in my personal and professional life during the previous few years – all of which – combined – led me to determine that it was time for a change. And I resolved that after the first of the year I would resign my State Government position and pursue my dream of opening my own gallery. More on this next chapter of my life in the art world in part two of my essay.

CONCLUSION

The stories in this essay illustrate the convergence and connections that have scaffolded my journey in the art world. They demonstrate the interconnectedness that has given me the sense that I was part of something bigger than myself – a feeling which has sustained me throughout my career. The events I have chronicled serve as anecdotal reminders of how the seemingly most insignificant action can set in motion a chain of events that can profoundly affect the trajectory of one’s life. To fulfill a central intention of this paper I have set forth the following list of lessons I have learned and important takeaways from my own experience:

- Respecting and remembering the individuals you meet in the course of your life and work is essential. This is a field where a person is more likely to find professional opportunity among those with whom you are already acquainted. I note with a tinge of regret the times when I failed to maintain contact with people who could potentially be still playing a role in my life if I had stayed in touch – an effort that is much easier in the digital age.

- It is only by being mindful and staying in the moment that we are able to seize the moment when a confluence of factors occur that can alter the course of our life. What might be seen as just a serendipitous coincidence is really the universe organizing events around our intentions. As my sister and mentor, Julia Rutherford-Silvers, stated in a recent email exchange: "Serendipity – often mistaken as some sort of happenstance – is revealed through wayfinding to find the true pathway to where you are, as well as reveal the pathway to where you want to be.”

- I have learned, often the hard way, that it is helpful to keep one’s ego in check as much as possible. Maintaining a sense of humility allows us to collaborate and learn from others and opens us up to learning from our own mistakes – and I have come to appreciate the fact that we learn as much from our mistakes as we do from our successes. If our egos are too big it can also keep us from being willing to spend time paying dues in a profession were this is a central dynamic.

- Keep track of all the experiences you have and all the projects you are involved in – even those that seem inconsequential at the time. This is the material that will make your resumé rich, and enhance your positon for opportunities in the future. Keeping a record also demonstrates the skillsets you are acquiring, which simultaneously makes you a more marketable quantity and builds confidence and self-esteem.

- There is seldom a downside to helping artists, so long as in doing so you are remaining true to your own values and respecting healthy boundaries you have established. We are not always in a position to be magnanimous but when we are it is deeply satisfying to offer assistance without expectation of anything in return. It is part of what makes the art world go ‘round.

I have been around long enough to understand that things that seem worst at time later turn out to be the best thing that could have happened. This philosophy can be hard to accept when you are going through something difficult but it can help keep you from giving up hope. The phrase “Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end” is attributed to Roman philosopher Seneca and continues to be a recurring theme in my life. (Seneca, 2017)

In conclusion, I would like to share the following passage by 19th Century author James Allen from his book As a Man Thinketh, which eloquently sums up why I have chosen the path outlined in this essay:

“Composer, sculptor, painter, poet, prophet, sage,

these are the makers of the after-world, the architects of heaven.

The world is beautiful because they have lived;

without them, laboring humanity would perish.”

|

Click here to view Abstract, Acknowledgements, Dedication, and Bibliography

|